How do newborn senses compare with our own? Babies don’t see colors quite like we do, and their vision is blurry. They have more trouble picking out speech from background noise. Yet newborns are fascinated by the visual world, and they show remarkable abilities to recognize different sights, sounds, textures, and odors.

Some self-appointed experts have taken a dangerously dim view of newborn babies. Until the late 20th century, many medical authorities actually denied that newborns can feel pain (Rodkey and Ridell 2013).

Thankfully, modern science has debunked that notion, and shed light on remarkable abilities of infants.

So what can babies feel, see, hear, smell and taste? What do babies notice about the world, and how does sensory information influence their development? Here is an evidenced-based look at the newborn senses.

The newborn sense of touch

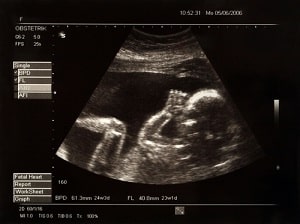

Ultrasound confirms that babies experience the sense of touch long before they are born.

If a pregnant woman rubs her belly, her fetus can feel the vibrations. And babies engage in lots of self-touch, especially during the third trimester, when their skin may become more sensitive to stimulation (Marx and Nady 2015).

After birth, babies continue to explore the world through touch, and it’s clear that touch is a powerful social and emotional signal.

For instance, when researchers brushed sleeping babies on the leg with a slow, gentle stoke, it activated parts of the brain that specialize in processing social and emotional information (Tuulari et al 2019; Jönsson et al 2018).

And experiments show that affectionate, skin-to-skin contact can soothe newborns in pain, and help babies grow and thrive (Johnston et al 2017; Conde-Agudelo and Díaz-Rossello 2016).

In fact, affectionate touch may help reverse some of the adverse affects of prenatal stress, and protect at-risk babies from developing an abnormal stress response system.

Prenatal stress can alter the functioning of a baby’s stress-regulating genes. So can postpartum depression. But when researchers have tracked babies over time, they’ve found that high levels of affectionate touch (stroking) reverse the effect (Murgatroyd et al 2015).

Moreover, babies who receive lots of affectionate touch tend to show less emotional negativity as they get older, and they develop fewer symptoms of anxiety and depression (Sharp et al 2012; Sharp et al 2015; Pickles et al 2017).

So cuddling your newborn isn’t just natural, intuitive, and humane — the right thing to do. It’s also a form of environmental programming, one that increases your baby’s chances of developing greater emotional health and resilience.

What about the more investigative aspects of touch? The information that babies gather about their world when they feel textures, or grasp something in their fingers?

Babies use their sense of touch to “fill in” what they don’t yet know about an object’s visual appearance.

If I handed you a small object and let you touch it — without giving you the chance to see it — could you figure out what it looks like?

It’s an old party game, and one that you might assume requires lots of previous practice. You need to be able to take purely tactile information and then translate it into a 3-D image in your mind.

Surely this is beyond the ability of a newborn, right?

Wrong. In fascinating experiments, Arlette Streri and her colleagues discovered that newborns are capable of inferring the appearance of an object from touch alone (Streri 2003; Streri and Gentaz 2004; Sann and Streri 2007; San and Streri 2008).

Experimenters gave each baby a simple object to handle: either a solid wooden cylinder, or a solid wooden prism with a triangular base. The babies touched only one type of object, and they couldn’t see what they were touching.

Then came the test.

The newborns weren’t holding objects anymore. Instead, they were looking at objects. In successive presentations, and experimenter would jiggle either the cylinder or the prism in front of the baby, while a camera recording infant eye movements.

Would the newborns react different to the objects? Show signs that they recognized whichever object they had perviously held in their hands?

Remarkably, they did. In trial after trial, the babies reacted as if they were already familiar with the object they’d touched. They didn’t look at it much, focusing their attention instead on the other item — whichever shape they hadn’t handled previously.

Just as interesting, the babies couldn’t perform this trick in the other direction. If a baby was allowed only to look at a new object, he wasn’t able to recognize it later by touch alone. In another words, newborns couldn’t start with purely visual information and translate it into tactile information.

The results suggest that newborns use touch to help make sense of visual information. When a baby touches your face, she may be learning how to recognize it visually.

But does this mean your newborn senses the world primarily through touch?

Clearly not. In fact, when it comes to social interactions, babies seem to find touch more reassuring if it comes as part of a package — one that includes affectionate cuddles, friendly eye contact, talking, and rocking.

Newborns notice how we touch them — and they get stressed when we do it the wrong way.

In an experiment on newborns, researchers randomly assigned infants to one of two treatments. Half the babies were stroked by a silent, uncommunicative caregiver. The other half were also stroked, but in combination with rocking, eye contact, and soothing speech.

The babies who received the combination package experienced a drop in stress hormone levels. The babies who were stroked in isolation experienced a stress hormone surge (White-Traut et al 2009).

And babies can also get stressed when we’re too pushy — when we ignore their desire for downtime, touching and stimulating them in ways they don’t want (Feldman et al 2010). So the key is to pay attention to your baby’s signals, and provide him with the sort of touching that he finds enjoyable or soothing.

For more information, see these Parenting Science tips for reducing stress in babies.

The newborn sense of sight: What can babies see?

You’ve probably heard that newborn eyesight is relatively poor, and it’s true.

Do newborns see in 3-D?

No. Stereoscopic depth perception (perceiving the world in “3-D”) doesn’t appear until approximately 16 weeks postpartum (Jandó et al 2012; Streri et al 2012; Held et al 1980).

Do newborns see color?

Yes, but to a limited degree. Color discrimination is very poor immediately after birth, and develops gradually over a period of months (Johnson 2010).

For instance, when researchers tested 4-day old infants, they found these babies could successfully distinguish between white and orange (i.e., light with a wavelength of 595 nm). But they failed to distinguish white from yellow-green colors (Adams et al 1991).

Similar studies have shown that many babies under 4 weeks of age have trouble telling the difference between

- white and dark blue,

- white and red,

- red and green, and

- red and yellow (Adams 1995; Clavadetscher et al 1988).

By 8 weeks, most babies possess better color perception. This is the age by which they can reliably distinguish the color red (wavelength 633 nm) from white, as well as turquoise blue (486 nm), and some blue-greens (496-516 nm).

But they still struggle with yellow and yellow-greens, as well as certain shades of purple (see Banks and Bennet 1988 for summary). Color abilities continue to develop throughout infancy and early childhood (Goulart et al 2008).

Does this mean your newborn baby is colorblind? No! This isn’t colorless vision. Contrary to the popular claim, newborns don’t see the world in black and white. But it’s a world with very little color, and more subtle contrast between hues.

What about visual acuity? How blurry do things look to a baby?

Newborns can see faces and large shapes, but their visual acuity is very poor compared with an adult’s.

To get a feeling for the difference, imagine a pattern of black-and-white stripes on a piece of paper. The stripes are just wide enough that you can fit two alternations — black/white/black/white — per centimeter.

The striped paper is placed against a solid, grey backdrop. You stand back a few feet and take a look. Can you still see the stripes, or do they disappear — blend imperceptibly into the background?

If you have normal vision, you will have no difficulty seeing the stripes. But the average newborn won’t be able to detect the stripes, not even if you hold the display 15 inches from her face.

To get a feeling for this, imagine a pattern of black-and-white stripes on a piece of paper. The stripes are just wide enough that you can fit two alternations — black/white/black/white — per centimeter.

To the baby, the stripe pattern is too fine. The stripes blur together (Cavallini et al 2002). An optometrist would rate her visual acuity at around 20/640 — a score that easily meets the threshold for being legally blind.

When do babies begin to see clearly? Research suggests that babies experience steady and steep gains over the first few months. By 6 months, the typical baby would score around 20/60 (Salomão et al 2008) — a major improvement.

Given these limitations, are newborns interested in the visual world?

Absolutely! Newborn might not see as well as adults do, but they are nevertheless fascinated by visual information.

Like the T. rex in Jurassic Park, newborns find moving objects to be especially interesting (Valenza et al 2015). They also show a special attraction to faces, and they can rapidly learn to recognize the faces of their caregivers.

In one study, researchers presented babies with video playbacks of two faces. One was the infant’s own mother. The other was the face of an unfamiliar woman (Bushnell et al 1989).

The infants—who ranged between 12 and 36 hours old—showed a clear preference for watching their mother’s face, as opposed to the face of the stranger. And this was true despite the fact that the faces were presented in silence, and without any olfactory cues. The babies couldn’t have been tipped off by their mother’s voice or scent.

Other studies have replicated these results, and offer insight into the visual clues that babies use to tell people apart: They are probably noticing differences in face shape, hairstyle, and color (Pascalis et al 1994).

The newborn sense of hearing

Babies develop the ability to hear long before they are born. In fact, they’ve listened so long, they aren’t just familiar with the sound of their mothers’ voices. They can pick out some of the distinctive patterns of their mother’s native language, and they may even mimic these patterns when they cry!

In a study of French and German babies, researchers found that French newborns produced cries with a rising melodic contour, much the way French speakers do when they utter a sentence. The German babies, by contrast, produced typically Germanic-sounding cries — with a falling intonation (Mampe et al 2009).

That’s pretty amazing stuff, and there’s more: Newborns pay us special attention when we speak to them in “parentese” — the slow, repetitive, musical mode of talking that many parents find natural when addressing an infant. As I note elsewhere, it’s likely that “parentese” helps babies learn about our emotions. It may also help them decipher language.

But don’t be fooled. Babies don’t start life with exactly the same listening abilities as adults. Babies have more trouble picking out speech from background noise (Erickson and Newman 2018). To help babies learn language, we need to talk with them, one-on-one, in environments that are free from noise pollution.

The newborn senses of smell and taste

As far as we know, there is nothing inferior about a newborn’s sense of smell.

For instance, when researchers have presented newborns with unfamiliar odors, the babies’ brains responded much like our own (Adam-Darque et al 2018). And in at least one respect, newborns have outperformed adults:

Experiments suggest that newborns are actually better at detecting the odor components in human sweat than adults are (Loos et al 2017).

Other research shows that newborn babies can recognize the smell of amniotic fluid (Varendi et al 1997). They can also distinguish between the scent of breast milk and formula.

When researchers presented formula-fed newborns with two different odors — the scent of breast milk from an unfamiliar woman, and the scent of a familiar infant formula — the babies showed a preference for the odor of human milk (Marlier and Schaal 2005).

Moreover, the scent of breast milk appears to have a calming, painkilling effect on newborns (Baudesson de Chanville et al 2017; Neshat et al 2016; Nishitani et al 2009). And if you familiarize newborns to an odor shortly after birth, they can develop a fondness for it.

In one experiment, newborns were introduced to the scent of chamomile while they were nursing. Days later, their attraction to the scent of chamomile was as strong as their attraction to the scent of breast milk (Delaunay-El Allam et al 2006). Similar results have been reported for the scent of vanilla (Goubet et al 2007).

What about identifying individuals? Can newborns recognize their caregivers by scent?

It seems that they can. In one breast milk study, newborns undergoing a painful procedure (a heel prick) were soothed by the smell of milk. But only if the milk came from their own mothers (Nishitani et al 2009).

In another study, newborns were presented with the odors of different breast milk samples–samples donated by their mothers and by other, unfamiliar women. The babies mouthed more in response to their own mothers’ odors, and the amount of prior exposure made a difference:

Those who’d experienced more than 50 minutes of contact showed a greater difference in mouthing (Mizuno at al 2004).

And the sense of taste? How do newborns respond to flavors?

As every foodie knows, our experience of flavor is influenced by our sense of smell. For example, differences in odor account for much of what makes an apricot taste different than a peach.

But of course it isn’t only about odor. We also have taste buds, and these help us detect at least five dimensions — sweetness, saltiness, bitterness, sourness, and umami (a savory, hearty taste associated with glutamate, and found in meats, milk products, and mushrooms).

A newborn senses all of these dimensions except one: Experiments suggest that babies can’t taste salt until they are about 4 months old (Beauchamp et al 1986).

As for the rest, newborns are especially partial to sweetness. In fact, when babies are given a sugar solution immediately before a painful procedure–like a heel prick–they cry less. Newborns also seem to like the taste of glutamate, which is found in breast milk (Beauchamp and Pearson 1991).

By contrast, newborns react negatively to some (but not all) bitter substances. And when a newborn senses a sour substance, he is likely to pull away and grimace (Steiner 1977).

Does the sense of taste have any practical consequences for a newborn? You might not think it matters much, since young infants consume only breast milk of baby formula. But experiments indicate that the flavors in a mother’s diet get passed along in the breast milk, and the babies notice.

Early exposure to these “added” flavors may help babies develop preferences for healthful foods later on. You can read more it here.

What else can newborns do?

Immediately after birth, babies show remarkable social abilities. For more information, see this evidence-based review of how a newborn senses the social world.

And what about thinking? Problem-solving? Memory? Learn more about your baby’s fascinating intellectual abilities in my article, “Newborn cognitive development: What babies are thinking and learning.”

References: The newborn senses

Adam-Darque A, Grouiller F, Vasung L, Ha-Vinh Leuchter R, Pollien P, Lazeyras F, Hüppi PS. 2018. fMRI-based Neuronal Response to New Odorants in the Newborn Brain. Cereb Cortex. 28(8):2901-2907.

Adams RJ. 1995. Further exploration of human neonatal chromatic-achromatic discrimination. J Exp Child Psychol. 60(3):344-60.

Adams RJ, Courage ML, Mercer ME. 1991. Deficiencies in human neonates’ color vision: photoreceptoral and neural explanations. Behav Brain Res. 43(2):109-14.

Banks MS and Bennett PJ. 1988. Optical and photoreceptor immaturities limit the spatial and chromatic vision of human neonates. J Opt Soc Am A. 5(12):2059-79.

Beauchamp, G K and Pearson, P.1991. Human development and umami taste. Physiol Behav. 49(5):1009-12.

Beauchamp GK, Cowart BJ, Moran M. Developmental changes in salt acceptability in human infants. Dev. Psychobiology 1986; 19:17-25.

Cavallini A, Fazzi E, Viviani V, Astori MG, Zaverio S, Bianchi PE, Lanzi G. 2002. Visual acuity in the first two years of life in healthy term newborns: an experience with the teller acuity cards. Funct Neurol. 17(2):87-92.

Clavadetscher JE, Brown AM, Ankrum C, Teller DY. 1988. Spectral sensitivity and chromatic discriminations in 3- and 7-week-old human infants. J Opt Soc Am A. 5(12):2093-105.

Conde-Agudelo A and Díaz-Rossello JL. 2016. Kangaroo mother care to reduce morbidity and mortality in low birthweight infants. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2016 Aug 23;(8):CD002771.

Delaunay-El Allam M, Marlier L, and Schaal B. 2006. Learning at the breast: preference formation for an artificial scent and its attraction against the odor of maternal milk. Infant Behav Dev. 29(3):308-21.

Erickson LC, Newman RS. 2017. Influences of background noise on infants and children Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 26(5):451-457

Feldman R, Singer M, and Zagoory O. 2010. Touch attenuates infants’ physiological reactivity to stress. Dev Sci. 13(2):271-8.

Goulart PR, Bandeira ML, Tsubota D, Oiwa NN, Costa MF, Ventura DF. 2008. A computer-controlled color vision test for children based on the Cambridge Colour Test. Vis Neurosci. 25(3):445-50.

Held R, Birch E, Gwiazda J. 1980. Stereoacuity of human infants. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 77(9):5572-4.

Jandó G, Mikó-Baráth E, Markó K, Hollódy K, Török B, Kovacs I. 2012. Early-onset binocularity in preterm infants reveals experience-dependent visual development in humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 109(27):11049-52.

Jönsson EH, Kotilahti K, Heiskala J, Wasling HB, Olausson H, Croy I, Mustaniemi H, Hiltunen P, Tuulari JJ, Scheinin NM, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Nissilä I. 2018. Affective and non-affective touch evoke differential brain responses in 2-month-old infants. Neuroimage. 169:162-171.

Johnson SP. 2010. How Infants Learn About the Visual World. Cogn Sci. 34(7): 1158-1184.

Johnston C, Campbell-Yeo M, Disher T, Benoit B, Fernandes A, Streiner D, Inglis D, Zee R. 2017. Skin-to-skin care for procedural pain in neonates. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2:CD008435.

Loos HM, Doucet S, Védrines F, Sharapa C, Soussignan R, Durand K, Sagot P, Buettner A, Schaal B. 2017. Responses of Human Neonates to Highly Diluted Odorants from Sweat. J Chem Ecol. 43(1):106-117.

Marlier L and Schaal B. 2005. Human newborns prefer human milk: conspecific milk odor is attractive without postnatal exposure. Child Dev. 76(1):155-68.

Marx V and Nagy E. 2015. Fetal Behavioural Responses to Maternal Voice and Touch. PLoS One. 10(6):e0129118.

Mizuno K, Mizuno N, Shinohara T, and Noda M. 2004. Mother-infant skin-to-skin contact after delivery results in early recognition of own mother’s milk odour. Acta Paediatr. 93(12):1640-5.

Murgatroyd C, Quinn JP, Sharp HM, Pickles A, Hill J. 2015. Effects of prenatal and postnatal depression, and maternal stroking, at the glucocorticoid receptor gene. Transl Psychiatry. 5:e560.

Neshat H, Jebreili M, Seyyedrasouli A, Ghojazade M, Hosseini MB, Hamishehkar H. 2016. Effects of Breast Milk and Vanilla Odors on Premature Neonate’s Heart Rate and Blood Oxygen Saturation During and After Venipuncture. Pediatr Neonatol. 57(3):225-31.

Nishitani S, Miyamura T, Tagawa M, Sumi M, Takase R, Doi H, Moriuchi H, and Shinohara K. 2009. The calming effect of a maternal breast milk odor on the human newborn infant. Neurosci Res. 63(1):66-71.

Pickles A, Sharp H, Hellier J, Hill J. 2017. Prenatal anxiety, maternal stroking in infancy, and symptoms of emotional and behavioral disorders at 3.5 years. Eur Child Adolesc Psychiatry. 26(3):325-334.

Porter RH, Makin JW, Davis LB, Christensen KM. 1991. An assessment of the salient olfactory environment of formula-fed infants. Physiol Behav. 50(5):907-11.

Romantshik O, Porter RH, Tillmann V, Varendi H. 2007. Preliminary evidence of a sensitive period for olfactory learning by human newborns. Acta Pædiatrica. 96( 3):372 – 376.

Salomão SR, Ejzenbaum F, Berezovsky A, Sacai PY, Pereira JM. 2008. Age norms for monocular grating acuity measured by sweep-VEP in the first three years of age. Arq Bras Oftalmol. 71(4):475-9.

Sann C and Streri A. 2008. The limits of newborn’s grasping to detect texture in a cross-modal transfer task. Infant Behav Dev. 31(3):523-31.

Sann C and Streri A. 2007. Perception of object shape and texture in human newborns: evidence from cross-modal transfer tasks. Dev Sci. 10(3):399-410.

Sharp H, Pickles A, Meaney M, Marshall K, Tibu F, and Hill J. 2012. Frequency of infant stroking reported by mothers moderates the effect of prenatal depression on infant behavioural and physiological outcomes. PLoS One. 7(10):e45446.

Sharp H, Hill J, Hellier J, Pickles A. Maternal antenatal anxiety, postnatal stroking and emotional problems in children: outcomes predicted from pre- and postnatal programming hypotheses. Psychol Med. 2015 Jan;45(2):269-83.

Streri A. 2003. Cross-modal recognition of shape from hand to eyes in human newborns. Somatosens Mot Res. 20(1):13-8.

Streri A and Gentaz E. 2004. Cross-modal recognition of shape from hand to eyes and handedness in human newborns. Neuropsychologia. 42(10):1365-9.

Streri A, de Hevia MD, Izard V, Coubart A. 2012. What do We Know about Neonatal Cognition? Behav Sci (Basel). 3(1):154-69.

Steiner JE. 1977. Facial expressions of the neonate infant indicate the hedonics of food – related chemical stimuli. In: Weiffenbach, J.M. (ed): Taste and Development: The Genesis of Sweet Preference. Washington, D.C., U.S. Government Printing Office.

Tuulari JJ, Scheinin NM, Lehtola S, Merisaari H, Saunavaara J, Parkkola R, Sehlstedt I, Karlsson L, Karlsson H, Björnsdotter M. 2019. Neural correlates of gentle skin stroking in early infancy. Dev Cogn Neurosci. 35:36-41

Valenza E, Otsuka Y, Bulf H, Ichikawa H, Kanazawa S, Yamaguchi MK. 2015. Face Orientation and Motion Differently Affect the Deployment of Visual Attention in Newborns and 4-Month-Old Infants. PLoS One. 10(9):e0136965.

Varendi H, Porter RH, Winberg J. 1996. Attractiveness of amniotic fluid odor: evidence of prenatal olfactory learning? Acta Paediatr. 85(10):1223-7.

Varendi H and Porter RH. 2002. The effect of labor on olfactory exposure learning within the first postnatal hour. Behav Neurosci. 116(2):206-11.

Content of “The newborn senses: What can your baby feel, see, hear, smell, and taste?” last modified 8/17

Image credits for the Newborn Senses:

Title image of newborn with funny facial expression by Lemmer_Creative /istock

image of ultrasound by Mikael_Damkier / shutterstock

image of newborn and adult hands by GODS_AND_KINGS / istock

image of orange, three dimensional shapes by Parenting Science

image of black and white stripes against grey background by Parenting Science

Small portions of this article are derived from an earlier work by the same author, “Wired for fast track learning? The newborn senses of taste and smell” (2011).

Content of “The newborn senses” last modified 10/2020