Motor milestones mark exciting transitions in our children’s lives — those time points when a child demonstrates the ability to carry out certain movements with their muscles. But there is no single, universal, milestone timeline that all children follow. For example, studies indicate that at least 50% of infants can

- roll over (from back to belly, or belly to back) by 4-5 months

- sit up, unsupported, by 6 months,

- crawl on hands and knees by 8 and a half months,

- stand, unassisted, by 11 months, and

- walk, unassisted, by 12 months.

Yet the timing and expression of motor development varies substantially from baby to baby – and from one culture to the next. There are babies who have learned to roll over when they are only 2 months old, and babies who stand (unassisted) when they are less than 8 months old. There are societies where infants never learn to crawl, and societies where children don’t normally begin walking until well past 18 months (Nelson et al 2004; Rachwani et al 2020; Kaplan and Dove 1987).

What’s going on here? We can definitely rule out the idea that all healthy babies develop at the same rate. Clearly, that isn’t happening. We can also reject the notion that individual children are biologically programmed to hit their motor milestones at specific, predetermined ages.

As we’ll see below, there is strong evidence showing that motor development is influenced by parenting practices and other environmental factors: Children develop skills faster when they get lots of opportunities to practice.

So what does this mean if we want to know what to expect, and find out if our own children are on track?

Basically, it means that we need to think about motor milestones as likely to occur within certain time windows – sometimes relatively broad time windows. Individuals develop at their own pace, depending on their personal characteristics and experiences.

In this article, we will go over the development time windows during which most children achieve major motor milestones – both gross motor milestones, and fine motor milestones. Then we’ll talk about when to be concerned about the possibility of a motor delay. I’ll include an age-by-age timeline of when to talk to your pediatrician if your baby seems to be lagging, based on the latest, expert recommendations. Finally, we’ll talk about the reasons that individual children vary in the timing of milestones, and I’ll present some evidence-based tips for supporting the development of motor skills.

Gross motor milestones: Examples of postural and locomotary milestones

Gross motor milestones depend on the coordination of large muscles in the legs, trunk, and arms. They include modes of locomotion, like crawling, walking, and running. But they also include motor skills related to posture, like being able to hold your head erect, sitting up without support, and standing.

What are the major gross motor milestones – the milestones that parents are supposed to notice and track? Historically, pediatricians and developmental scientists have emphasized these postural and locomotory milestones:

- Lifts head when lying on belly

- Pushes up on forearms or elbows while lying on belly, elevating chest

- Rolls over

- Sits without support

- Crawls

- Stands with support

- Pulls self up into a standing position

- Climbs (onto a low chair or other piece of furniture)

- Stands without help or support

- Walks alone, without support

- Runs

- Jumps with both feet

- Hops

When should we expect children to achieve gross motor milestones?

Understanding the range of milestone “ages”

Individual variation makes this tricky, even if we restrict ourselves to children living in the same society. For instance, take the first milestone – a baby lifting his or her head while lying prone (belly down). A study of Canadian babies suggests that around 5% of children can achieve this shortly after birth. Half can do it before they are 1.5 months old, and 95% will have reached this milestone by the time they are 4 months old (Rachwani et al 2020; Piper and Darrah 1994).

We could try to mash this up with a single number – an average – but that wouldn’t be very helpful for appreciating the range of what’s normal. A better way to represent the development of motor skills is to think in terms of developmental windows – time periods during which the vast majority of children achieve a given milestones.

So we can characterize the milestone, “Lifts head when lying on belly,” with a time window based on the statistics from the Canadian study. For children encountering conditions similar to those in Canada, we may expect that about 95% of children will achieve this motor milestone sometime between birth and 4 months (Piper and Darrah 1994).

This age range is roughly similar to what researchers have observed for children living in Africa, South Asia, and Central and South America, where about 10% of babies lying on their bellies were able to hold their heads up for at least a few seconds within the the first 3 weeks after birth, and 90% had achieved the milestone by 3 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

In the same way, researchers can use large data sets to estimate time windows for other gross motor milestones, including the following:

Examples of time windows for typical motor development

- Pushes up on forearms or elbows while lying on belly, elevating chest: 10% display this by 1.6 months, and 90% by 3.8 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

- Rolls over: 5% by 2 months, and 95% by 9 months (Piper and Darrah 1994)

- Sits without support: 10% by 4.6 months, and 90% by 7.5 months (WHO 2006b)

- Crawls (on hands and kneess): 10% by 6.1months, and 90% by 10.5 month (WHO 2006b)

- Stands with support (for at least 10 seconds): 10% by 5.4 months, 90% by 10.5 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

- Pulls self up into a standing position: 10% by 5.8% months, and 90% by 10.7 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

- Climbs (onto a low chair or other piece of furniture): 10% by 7.5 months, and 90% by 14 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

- Stands without help or support: 10% by 8.8 months, 90% by 14.4 months (WHO 2006b)

- Walks alone, without support: 10% by 10 months, and 90% by 14.4 months (WHO 2006b)

- Runs: 10% by 12.2 months, and 90% by 24 months

- Jumps with both feet: 10% by 24.7 months, and 90% by 42.7 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

- Hops (at least three steps forward): 10% by 28.6 months, and 90% by 52.1 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

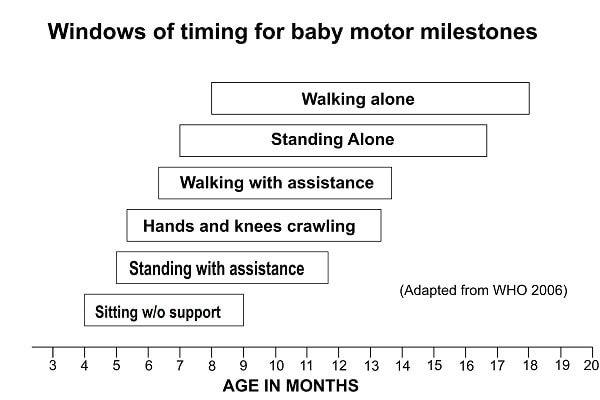

If you prefer a more visual approach, here’s an infographic I made to illustrate, adapted from a figure published by the World Health Organization (WHO 2006b). It shows the time windows during which approximately 98% of infants reach 6 gross motor milestones.

As you can see, some gross motor milestones tend to occur earlier than others, but the windows are wide, and they overlap each other. The resulting picture doesn’t predict when your baby will hit any particular milestone – not in any fine-grained sense. But it provides us with a realistic time range.

What about object manipulation skills? When do they emerge?

The motor skills we’ve mentioned so far are concerned with posture or locomotion. But of course there are also motor skills that involve the manipulation of objects. In some cases, these abilities depend on gross motor ability, but they typically require fine motor development, too — the coordination of small muscles in the hand, eye, and (sometimes) the mouth or feet. What are examples to watch for?

Holding objects (with help), and attempting to reach for objects

Two-month-old babies can hold onto small objects – if we place these objects directly into their hands. And they are likely to bring the items up to their mouths to investigate (Rochat 1989). But the grasp of a young infant isn’t very secure or reliable. When babies’ arms flail around, they are likely to lose their grip on whatever they are holding. Approximately 10% of infants can make an unsuccessful reach by 1.6 months, and 90% have achieved this milestone by 4 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

Greater competence with holding, reaching, and grabbing

Between the ages of 3 and 6 months, most babies will have developed the manual dexterity to hold onto and shake a toy. They are also developing the ability to move an object back and forth between hands. In international research, about 10% of infants could pass a toy between their hands by 4 months, and 90% could do it by 7 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

Around 10% of babies can successfully reach for a stationary object by 3 months, and 90% have caught up with this milestone by 5 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2). But their movements are jerky, and babies aren’t yet good at catching a moving object. Babies don’t yet understand how to grasp large objects efficiently – they don’t show a preference for doing it with both hands.

Between 6 and 9 months, these “grabbing” skills improve considerably. Babies become proficient at catching hold of rolling objects. For instance, they can grab rolling balls, and judge when some balls are rolling too fast to catch (van Hof et al 2008). By 11 months, babies also show better planning for picking up large objects – they consistently reach with both hands at once (Fagard and Jacquet 1996).

Kicking a ball

Kicking a ball is more challenging than rolling it, in part because you must be standing up while you do it. So parents don’t usually observe this until children are well beyond their first birthdays. In international tests, kids were challenged to see if they could kick a ball while keeping their balance. About 10% of children could do this by 12 months, but it wasn’t until kids were more than 17 months old (and, in some tests, more than 25 months old) before 90% of them could achieve this milestone (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2)

Learning to throw (and catch)

In a small study of children in the United Kingdom, researchers observed toddlers between the ages of 15 and 30 months throwing objects overarm. All kids could do it, but kids didn’t “put their whole body” into the effort. They usually moved their arms in isolation, without stepping into the throw, or moving their torsos. Older children tended to release items at higher speeds (Marques-Bruna and Grimshaw 1997).

As you might expect, developing good throwing aim, and the ability to catch, depends on hand-eye coordination — a classic hallmark of fine motor skills. And, according to international research, the time window for these motor skills is quite broad. About 10% of toddlers can perform at least 3 throws and 3 catches by the time they are 15 months, and 50% can do this by the age of 27.4 months. By 45.5 months, 90% of children have reached this milestone (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

Refinements of fine motor control and tool use

Ever-improving grasping skills

By between 5 and 10 months, most babies are showing off a number of fine motor skills. For instance, if you present infants with a small piece of food on a table surface, about 10% of them can “rake” the item towards themselves (a sweeping motion using all of their fingers) by about 5 months. Research suggests that 90% of children can do this by 10-13 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

During this period, babies also begin developing the ability to grip small objects between the thumb and index finger – the so-called “pincer grasp”. Many babies can drink from a cup (albeit with help!), and they are figuring out how to eat with a spoon.

But their attempts are awkward. For instance, if you provide babies with a loaded spoon, they are likely to pick it up by the bowl end – not the handle (McCarty et al 2001; van Roon et al 2003). Moreover, they will hold onto the spoon with a fist grip, not a precision (pincer) grasp. By 14 months babies are more adept. They might still hold the spoon in a fist grip, but they’ve learned how to hold it by the handle (van Roon et al 2003).

Scribbling

By 11 to 12 months, about 50% of babies can use a writing implement (like a crayon on pen) to draw random-looking marks and dots. But just as we saw with learning to throw and catch, the age at which children begin “scribbling” varies quite a lot (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2), no doubt depending on their opportunities to practice. By 18 months, scribbling efforts may become more controlled and organized, and may include straight lines and zig-zags (Dunst and Gorman 2009). More complex drawings – of geometric shapes, and figures with identifiable features (like a blob creature with legs) – develop slowly, and may not appear until a child is three years old (Dunst and Gorman 2009).

Stacking blocks

In a study tracking the fine motor development of 37 infants in the United States, researchers found that more than 85% of the children had begun stacking at least one block on top of another between the ages of 10 and 14 months. By 18 months, about 40% of the children could create block towers composed of 3 elements or more. By 24 months, more than 85% of the kids had reached this fine motor milestone (Marcinowski et al 2019). International research suggests that 90% of children can create a 6 block tower by the age of 37.6 months (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

Using hands to twist things

This is yet another fine motor skill that varies widely. For instance, in a study where children were asked to screw on the lid to a jar — and then screw it back off — about 10% could do this by about 21.7 months. But it took until 43.5 months for 90% of the children to master both tasks (Lancaster et al 2018, supplement 2).

If a child’s development seems slow, when should you be concerned?

First, you need to trust your intuitions. If something seems wrong or worrying, talk to your pediatrician. If it turns out that your baby is having problems, early intervention can make a big difference.

But what if you’re merely noticing that your baby is taking longer than most to reach a particular motor milestone. At what point should your baby should be screened for a possible developmental delay?

In the absence of any other signs or concerns, one rule of thumb is to pay attention to the 90th percentile – the age by which 90% of children have achieved a given milestone (Sices 2007). Another approach is to set the bar lower, at the age when a milestone has been reached 75% of the population (Zubler et al 2022).

Either way, the idea is to compare children, and then focus on individuals who are slower than a selected percentage of their peers. If a child still hasn’t reached a milestone by the specified age, it doesn’t mean that child is especially likely to have a developmental problem. But it’s an indication to move forward with screening. As noted, early intervention can be important, so it makes sense to take a proactive approach.

Below are some of the latest, evidence-informed milestone recommendations, as proposed by researchers working for the American Academy of Pediatrics and the Center for Disease Control (Zubler et al 2022). Note that the researchers are using a 75% criterion, and that the ages represent the cut-off dates for observing the given milestones. If your child has not reached a milestone by the listed date, that’s reason to talk with your medical provider.

Motor milestone timeline: At what age should you consult your pediatrician (if you child hasn’t yet demonstrated a particular skill)?

2 months

- Holds up head when lying on belly

- Moves every limb (both arms and both legs)

- Briefly uncurls fingers (opening up the hand for a split second before relaxing again)

4 months

- Can hold head steady, without support, when being held

- Can control arms enough to reach and take a swing at a toy

- Pushes up on forearms or elbows while lying on belly, elevating chest

6 months

- Rolls over (from belly to back)

- Pushes up with arms straightened while on belly

- Leans on hands to keep steady while sitting

9 months

- Can get into a sitting position without help

- Sits up without support

- Can transfer objects from one hand to the other

- Uses fingers to sweep or rake an object towards self

12 months

- Pulls self up to a standing position

- Walks around while holding onto furniture (also called “cruising”)

- Can drink from a lidless cup, while you hold it for him

- Picks up objects by holding them between the thumb and pointer finger

15 months

- Takes first steps without support (but not necessarily walking yet)

- Uses fingers to eat (e.g., picking up a piece of breakfast cereal and bringing it to the mouth)

18 months

- Can walk without any help – without hanging onto a person or grasping the furniture

- Can climb onto a sofa or chair without help

- Can scribble when given a writing implement (like a crayon)

- Can drink from a cup without a lid, without help (but may spill sometimes)

- Tries to use a spoon during feeding (but not yet proficient)

24 months

- Can kick a large ball

- Runs

- Can walk up a few stairs (with or without assistance)

- Uses a spoon to eat

30 months

- Capable of jumping in the air with both feet

- Can take some clothing off without help (like pulling off loose pants)

- Can use hands to perform twisting actions (such as turning a knob or unscrewing a lid)

- Can turn the pages of a book, one at a time

3 years

- Can “string items together” (e.g., threading a cord through the holes in a set of large, wooden beads)

- Puts some clothing on without assistance

- Can use a fork

4 years

- Able to catch a ball consistently (e.g., can catch most “easy” tosses)

- Can unbutton some buttons

- Can pour water for himself, or serve herself food, with supervision

- Holds writing implements (e.g., a crayon) between thumb and forefinger

5 years

- Can hop on one foot

- Can button some buttons

What about the order of motor milestones? Is there something wrong if a child seems to skip a step, or experiences a reversal?

Not necessarily. Babies don’t always hit these milestones in the same order, and one of the milestones – crawling – isn’t even universal.

If you look at the time window graphic, you might reasonably assume that your baby will hit gross motor milestones in the following sequence:

(1) sitting up without support; (2) crawling on hands and knees; (3) standing with assistance; (4) walking with assistance; (5) standing without support; and (6) walking without support.

And indeed, when the World Health Organization (WHO) tracked the development of babies in 5 countries (Ghana, India, Norway, Oman and the USA), this pattern was found in the largest percentage of infants – about 42% of them.

But more than a third of the babies achieved milestone #3 (standing with assistance) before they crawled. Almost 9% of the babies also hit milestone #4 (walking with assistance) before crawling.

Another 10% of babies mixed the order up in even more exotic ways, and approximately 4% of babies never crawled on their hands and knees (WHO 2006a).

Other studies have reported even higher rates of babies who never crawled — babies who were healthy and went on to walk within the normal time window.

So there isn’t a master sequence of motor development milestones that all babies follow. As motor development experts Karen Adolph and John Franchak (2016) explain:

“The milestone charts suggest an orderly, age-related march through a series of stages, but developmental pathways can differ and individual infants do not strictly adhere to the normative sequence derived from average onset ages. Infants can acquire skills in various orders, skip stages, and revert to earlier forms.”

Why is there so much variation?

Some of it is cultural.

For example, in some African countries, parents actively train their babies to sit, stand, and walk. They provide infants with lots of practice, and this appears to accelerate the development of upright posture (Super 1976; Bril and Sabatier 1986; Karasik et al 2015; Adolph and Robinson 2015).

The notion is supported by experimental work (Zelazo 1983). Newborn babies have a “stepping reflex”: If you hold a baby so that soles of his feet brush against the ground, the baby will spontaneously take steps — long before the baby is capable of standing under his own weight. The reflex usually disappears over time, but not if babies are given daily opportunities to practice the action, and such babies have reached the milestone of walking (without assistance) at an earlier age. (You can read more about learning to walk in my article, “When do babies start walking, and how does it develop?”)

So we’ve got evidence that parenting practices can speed up the emergence of sitting, standing, and walking. And the converse is also true: Caregiving can contribute to slower development of these milestones.

In places where parents adopt a hands-off approach – or actively prevent babies from moving around during the day – infants take longer to sit, stand, and walk independently (WHO 2006b; Mei 1994; Adolph and Robinson 2015; Adolf et al 2018).

What about crawling?

Environmental factors may play an especially big role in the development of crawling. In the contemporary United States, parents expect babies to crawl, and they provide them with opportunities to do so. But this isn’t true everywhere, and it probably wasn’t true for our hunter-gatherer ancestors.

Crawling outdoors – in a world inhabited by predators – wouldn’t have been a good idea, and indeed, contemporary hunter-gatherers don’t encourage their infants to crawl. As I explain in this guide to the development of crawling, it’s not unusual for babies to reject hands-and-knees crawling in favor of other methods of getting around – like scooting around on their bottoms, or rolling from place to place.

It’s also clear that motor milestones are influenced by genetics.

When researchers have controlled for the effects of culture and parenting, they’ve found that genetic factors have an important impact on the timing of motor milestones (Smith et al 2017).

Siblings don’t reach motor milestones at exactly the same time, even if they are raised under similar conditions. Individual differences in temperament, body fat composition, and other characteristics — characteristics influenced by genes — can affect a child’s activity patterns, leading some individuals to spend more time practicing developing motor skills.

What can parents do to promote motor development?

Give your baby lots of “tummy time.”

As I note in this article, it’s clear that “tummy time” is important. Babies develop better muscle control when they spend supervised time on their stomachs. It’s good for building neck strength, and it helps babies develop the ability to roll, crawl, and sit up from a lying position (Kuo et al 2008).

Help babies practice an upright posture.

We’ve also seen how parents can support the development of sitting and standing. Practice sessions – where you help your baby adopt an upright posture by providing support with your hands – may speed up development.

Help babies reach and grasp.

Not surprisingly, babies learn faster when we provide them with opportunities to touch, hold, and reach for objects.

For example, in experiments using mittens and toys covered in Velcro®, babies as young as 3 months have gotten extra practice handling objects that would ordinarily be hard to grasp. When parents encourage their babies to explore objects with such “sticky mittens,” babies have shown long-term developmental benefits (Needham et al 2017; Libertus et al 2015).

Let babies bang.

It’s noisy and obnoxious, but researchers think that babies develop important motor skills when they grab onto an object and bang away (Kahrs et al 2012). Just make sure the object is safe for your baby to use!

Encourage free play – and make yourself a visible, responsive, and non-bossy playmate.

Babies exercise more – and spend more time interacting with objects – when we provide them with the time and space to engage in free play (Adolf and Koch 2019). And babies benefit when we get down on the floor to interact with them.

More reading

For more in-depth, anthropologically-informed information about motor milestones, check out my articles on these subjects:

- When do babies sit up by themselves, and what can we do to help them reach this milestone?

- When do babies crawl, and how does crawling develop?

- When do babies start walking, and how does it develop?

- Gross motor skills: A developmental guide

And for other information about baby development, see this index to Parenting Science articles.

References: Motor milestones

Adolph K. 2008. Motor and physical development: Locomotion. In M.M. Haith and J.B. Benson (Eds), Encyclopedia of infant and early childhood development, M.M. Haith and J.B. Benson (Eds), San Diego: Academic Press, pp. 359-373.

Adolph KE and Robinson SR 2015. Motor development. In R. M. Lerner (Series Eds.) and L. Liben and U. Muller (Eds), Handbook of child psychology and developmental science: Vol. 2: Cognitive processes (7th ed.) New York: Wiley, pp. 114-157

Adolph KE and Hoch JE 2019. Motor development: Embodied, embedded, enculturated, and enabling. Annual Review of Psychology, 70, 141-164.

Adolph KE, Hoch JE, Cole WG. 2018. Development (of Walking): 15 Suggestions. Trends Cogn Sci. 22(8):699-711.

Bril B and Sabatier C. The cultural context of motor development: Postural manipulations in the daily life of Bambara babies (Mali) International Journal of Behavioral Development. 1986;9:439–453.

Dunst C and Gorman E. 2009. Development of infant and toddler mark making and scribbling. Cent. Early Learn. Lit. Rev. 2, 1–16.

Fagard J, Jacquet AY. Changes in reaching and grasping objects of different sizes between 7 and 13 months of age. British Journal of Developmental Psychology. 1996;14:65–78.

Kahrs BA, Jung WP, Lockman JJ. 2012. What is the role of infant banging in the development of tool use? Exp Brain Res. 218(2):315-20.

Kaplan H and Dove H. 1987. Infant development among the Ache of eastern Paraguay. Developmental Psychology, 23(2): 190–198.

Kuo YL, Liao HF, Chen PC, Hsieh WS, Hwang AW. 2008. The influence of wakeful prone positioning on motor development during the early life. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 29(5):367-76.

Lancaster GA, McCray G, Kariger P, Dua T, Titman A, Chandna J, McCoy D, Abubakar A, Hamadani JD, Fink G, Tofail F, Gladstone M, Janus M. 2018. Creation of the WHO Indicators of Infant and Young Child Development (IYCD): metadata synthesis across 10 countries. BMJ Glob Health. 3(5):e000747.

Libertus K, Joh AS, Needham AW. 2016. Motor training at 3 months affects object exploration 12 months later. Dev Sci. 19(6):1058-1066.

Marcinowski EC, Nelson E, Campbell JM, Michel GF. 2019. The Development of Object Construction from Infancy through Toddlerhood. Infancy. 24(3):368-391.

Marques-Bruna P and Grimshaw PN. 1997. 3-dimentional kinematics of overarm throwing action of children age 15 to 30 months. Percept Mot Skills. 84: 1267-1283.

McCarty ME, Clifton RK, and Collard RR. 2001. The beginnings of tool use by infants and toddlers. Infancy 2: 233-56.

Mei, J. 1994. The Northern Chinese custom of rearing babies in sandbags: implications for motor and intellectual development. In: vanRossum, J.; Laszlo, J., editors. Motor development: Aspects of normal and delayed development. Amsterdam: VU Uitgeverij.

Needham AW, Wiesen SE, Hejazi JN, Libertus K, Christopher C. 2017. Characteristics of brief sticky mittens training that lead to increases in object exploration. J Exp Child Psychol. 164:209-224

Nelson EA1, Yu LM, Wong D, Wong HY, Yim L. 2004. Rolling over in infants: age, ethnicity, and cultural differences. Dev Med Child Neurol. 46(10):706-9.

Rachwani J, Hoch J, and Adolph KE. 2020. Action in development: Plasticity, variability, and flexibility. In J. J. Lockman and C. S. Tamis-LeMonda (Eds.), The Cambridge handbook of infant development: Brain, behavior, and cultural context (pp. 469–494). Cambridge University Press.

Rochat R 1989 Object Manipulation and Exploration in 2- to 5-Month-Old Infants Developmental Psychology 25 (6): 871-884

Sices L. 2007. Use of developmental milestones in pediatric residency training and practice: time to rethink the meaning of the mean. J Dev Behav Pediatr. 28(1):47-52.

Smith L, van Jaarsveld CHM, Llewellyn CH, Fildes A, López Sánchez GF, Wardle J, Fisher A. 2017. Genetic and Environmental Influences on Developmental Milestones and Movement: Results From the Gemini Cohort Study. Res Q Exerc Sport. 88(4):401-407.

Super CM. 1976. Environmental effects on motor development: the case of “African infant precocity”. Dev Med Child Neurol. 18(5):561-7.

vam Hof P, Kamp J, Savelsbergh GJP. 2002. The relation of unimanual and bimanual reaching to crossing the midline. Child Dev. 73:1353–1362.

van Roon D, van der Kamp J, Steenbergen B 2003. Constraints in children’s learning to use spoons. In: Savelsbergh G, Davids K, van der Kamp J, Bennett SJ, eds. Development of Movement Co-ordination in Children: Applications in the Fields of Ergonomics, Health Sciences and Sport. Routledge, London: 75-93.

WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. 2006a. Assessment of sex differences and heterogeneity in motor milestone attainment among populations in the WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 450:66-75.

WHO Multicentre Growth Reference Study Group. 2006b. WHO Motor Development Study: windows of achievement for six gross motor development milestones. Acta Paediatr Suppl. 450:86-95.

Zelazo PR 1983. The development of walking: New findings and old solutions. Journal of Motor Behavior 15: 99-137.

Zubler JM, Wiggins LD, Macias MM, Whitaker TM, Shaw JS, Squires JK, Pajek JA, Wolf RB, Slaughter KS, Broughton AS, Gerndt KL, Mlodoch BJ, Lipkin PH. 2022. Evidence-Informed Milestones for Developmental Surveillance Tools. Pediatrics. 149(3):e2021052138.

Image credits for “Motor milestones”

image of baby starting to roll over by istock / Gwill

image of baby holding and using spoon by istock/ PeopleImages

charts (adapted from WHO 2006) copyright Parenting Science

content last modified 10/2023