It’s one of the most common assumptions that people make about baby sign language — that babies can sign before they can speak. But is it true?

Not necessarily. It might be true, but we need more research to settle the question. Moreover, even if signing does tend to emerge first, the difference in timing is probably not dramatic. Based on studies conducted so far, it appears that some babies may start practicing spoken language by 9 to 10 months, which overlaps with the onset of signing observed among infants who are hearing-impaired.

The takeaway? Learning to produce language is challenging, whether it is spoken or signed, and we don’t yet have compelling evidence to prove that one mode is easier than the other.

This doesn’t mean it isn’t worthwhile for families without hearing impairments to teach their babies some signs. On the contrary, it can be fun and rewarding. But it’s helpful to approach the project with realistic expectations. There’s little reason to think that signs (especially those borrowed from genuine sign languages) are intrinsically easier to learn than spoken words.

So let’s take a closer look, starting with what we know about the development of language.

By 6-10 months, many babies have begun repeating our speech sounds. They may also understand a variety of everyday words.

Babies are born with a package of powerful mechanisms for learning to speak. It’s a basic human trait, the hallmark of our species, and experiments show that babies begin learning about language while they are still in the womb.

Infants can hear their mothers’ voices during the latter stages of pregnancy, and, after birth, they demonstrate a familiarity with the distinctive sounds of their native language. The react differently to the same voice, depending on whether it’s speaking their mother’s native language, or a different, unfamiliar language.

From such beginnings, babies begin to analyze what we say to them. They begin to perceive that our streams of speech are divided up into distinct words. Eventually, by observing and interacting with us, they work out what specific words mean.

What’s the timeline? Experiments suggest that most babies understand quite a few words by the time they are 6 months old. And around this same time, some babies are also repeating basic speech syllables — a behavioral called “canonical babbling.”

So when do babies transition from speaking mere syllables, to speaking genuine words?

That’s tricky to document, because a baby’s early attempts are going to be inexact.

Babies aren’t going to produce words with the magnificent elocution of James Earl Jones. They are still mastering the muscles required to speak. Their first attempts are going to be approximations. At what point do we count an imperfect utterance as a real word?

The problem doesn’t arise when the word itself is very easy for babies to say. And here, enter “mama”: the word for “mother” in many languages around the world.

The word reappears in languages as different as Swahili and Chinese, most likely because it’s incredibly easy for the human infant to master. “Ma” is often the first syllable that a baby repeats, so families in a variety of places and cultures have used it to signify “mother.”

Similarly, the baby-friendly syllables “da” and “pa” have often been used to signify “father,” though there are cultures where “papa” means mother and “mama” means father (Hendery and McConvell 2013).

But most vocabulary isn’t easy for babies to pronounce, and that’s where we can run into grey areas.

For example, is “baba” a good enough approximation of the word “bottle”? Is that a true word?

If you’re a parent who notices that your baby says “baba” when she wants her bottle, then you’ll want to respond accordingly. It would be confusing if you pretended that you didn’t understand her. Babies need confirmation when they are closing in on the right answer. It’s how they learn.

But sometimes “baba” is just a random bit of babbling, and researchers who study the emergence of speech must find ways to sift those instances out. They need to establish a set of objective criteria for recognizing an utterance as a spoken word.

Can babies sign before they can speak? To answer this question, we need to apply similar standards about what counts as a spoken word or visual sign.

When babies begin to use signs, are they as competent as adults? Far from it (Bonvillian and Siedlecki 2000). Signing, like speaking, depends on important motor skills. A baby’s first signs are going to be approximations, just as a baby’s first spoken words are approximations. Children are still mastering the muscles required to gesture.

So if we want to compare the timing of signing and speaking, we need to make sure we’re applying similar standards. Whatever allowances we make for a child approximating a spoken word, we should also make for a child approximating a sign. And vice versa.

If you see a baby approximate the sign for “drink,” you may be impressed. But then you should also be impressed when that same baby approximates the spoken word for “bottle.”

I’ve seen a video on YouTube where a baby is doing both. Simultaneously. It’s a wonderful example of a baby’s early attempts at productive language. The mother says the baby is signing “bottle,” though of course the gesture is only approximate. To me, it looks like a rough match for the ASL sign for “drink.” Either way, the baby appears to be producing a rudimentary sign. Hooray!

But the baby is also vocalizing. She is saying “ba-ba,” which seems to be an approximation of the spoken word for “bottle.” So this baby is showing off two language skills at once — communicating simultaneously with speech and sign. Yet what’s the title of this video clip? The title that it was uploaded with on youtube?

“Baby sign language…asking for a bottle.”

The signing is highlighted in the title, while the speech isn’t mentioned at all. Why?

Maybe the person who uploaded the video was simply more interested in the development of signing. But clearly, we’re kidding ourselves if we watch a video clip like this and regard it as evidence that babies can sign before they can speak.

We can’t accept approximate attempts to sign as language, and yet dismiss similarly approximate attempts to speak as pre-linguistic babbling.

If we did that, it would be easy to support the claim that signing comes first. But the support would be phony — an artifact of the way we measure things.

So what about the research on first spoken words and first signed words? What do they tell us?

To date, the relevant information comes from two different populations — children with normal hearing who are learning to produce speech, and children who are learning sign language from their deaf, signing parents.

When babies learn sign language from deaf, signing parents, when do they produce their first, signed words?

There is precious little research documenting this, but thankfully some investigators have tried. In one study, John Bonvillian and his colleagues visited families at home to monitor the development of 11 children, and — on average — these babies produced their first signs at around 8.5 months postpartum (Bonvillian et la 1983). Using a combination of home visits and parental diaries, a second, smaller study (of 9 children) reported an average age of 8.2 months (Folven and Bonvillian 1991).

What about spoken language?

Once again, there isn’t a lot of research to go on. But we have some. For example, in multiple surveys of families with normal hearing, Rose Schneider and her colleagues asked more than 1500 parents to recollect the timing of their babies’ first spoken words.

The results? Across all surveys, 75% of babies were reported to have spoken their first word by the age of 10 months. And in the largest survey (of 1,000 parents) 25% of babies were claimed to have spoken their first word before the age of 8 months (Schneider et al 2015).

More recently, researchers monitored the development of 44 hearing children by collecting monthly audio recordings in their homes. Using this method, the earliest recorded spoken word was documented at around the age of 9 months. But the majority of infants hadn’t spoken their first words until they were at least 12 months old (Dailey and Bergelson 2023).

Evidence for earlier signing?

On the face of it, this research appears to confirm a tendency for babies to learn signs earlier than they learn spoken words (Lillo-Martin and Henner 2021). Although there is overlap between the groups (with some babies speaking their first words ahead of other infants producing their first signs), the group averages look different: just over 8 months for first signed words, versus up to12 months for first spoken words.

But we run into problems when we try to compare group averages in this way.

First, there’s the problem of sample size, which was especially small in the two signing studies. We can’t draw firm conclusions about the relative timing of signing, not on the basis of samples in the range of 9-11 individuals. We need a larger sample to be sure the results don’t reflect chance factors and statistical error.

Second, we have the problem of differing methodologies. Reseach based on parent self-reports and recollections may produce different results than research based on expert analysis of home visits and recordings. And, as noted above, we need a way to know that we’re applying similar levels strictness when deciding whether or not a baby’s attempt counts as a true sign or true word. That’s lacking here.

We see similar difficulties when trying to evaluate research about the number of words that babies learn over time.

For instance, Diane Anderson and Judy Reilly recruited families where both parents and infants were deaf, and the babies were exposed to signing from birth.

The parents were asked to fill out monthly questionnaires for five months total. What signs have you seen your baby produce this month?

Then the researchers calculated the average number of signs that babies produced during a given age range.

Based on data collected from five children between the ages of 15 and 16 months, the average (median) number of signs produced was 64, with individuals ranging between 30 and 102 signs (Anderson and Reilly 2002, p.89).

By contrast, in a larger study of speech development, researchers assessed a group of 16-month-old babies (more than 60 children in total) and found that the average (median) number of words spoken was about 40. Individual babies ranged between fewer than 10 words and more than 175 (Fenson et al 1994, pp. 37-39).

A mere glance at the average number of words produced in each study — 64 words versus 40 — makes it appear that signing has the advantage. But once again, we can’t directly compare these studies.

The average number of signs derives from a very small sample, and the range of individual variation is large in both studies. So it’s impossible to know if there is a real, underlying difference in the averages between groups. It might just be a statistical blip.

And regardless, it’s clear that there’s a lot of overlap among individuals.

Just as we saw with the emergence of first words, there are babies in the speech group who show advances over babies in the signing group.

As language researcher Richard Meier (2016) notes, it’s just too soon to say whether or not babies can learn to sign before they can learn to speak. We need more research to decide the question (Meier 2016).

Why are we so eager to believe that babies can sign before they can speak?

This is a fascinating question in its own right, and I don’t know the answer. But I have my suspicions.

There is the hype factor, if course. It’s exciting to hear bold claims about baby signing, and they might make us forget the obvious — that lots of babies perform equally impressive feats with spoken language.

But it seems to me there is more behind it. I get the impression that people think signing is intrinsically easier than speaking, that producing symbolic gestures is somehow less demanding than producing symbolic sounds. But why would this be true?

People seem to assume that speech is harder. That it’s harder to figure out, or harder to physically reproduce. Or both. But we really have no basis for assuming this.

We might if we were comparing the task of learning speech with the task of learning a small set of pantomime gestures — gestures that “act out” the thing being referenced.

It’s relatively easy to figure out what pantomime gestures mean. That’s why people who lack a common language often resort to pantomime.

But baby sign language programs aren’t typically based on pantomime.

Instead, they involve teaching babies signs borrowed from real sign languages, like ASL. And these signs are like the words we use in English and other spoken languages: Some signs offer clues about their meaning, but many don’t. As I explain elsewhere, the link between most signs and their referents is unclear.

Moreover, even when clues exist, they may require substantial background information to figure out. Background information that babies and toddlers lack.

For example, in many sign languages, the word for “bird” involves moving the fingers in a way that is meant to represent a bird’s beak opening and closing (Emmorey 2023). It’s an excellent example iconicity — a similarity between the form of a sign and it’s meaning. And I’m betting that many language learners will find that iconicity helpful.

But will the iconicity be as obvious to a very young child? If you think about it, we don’t often see birds opening and closing their beaks. Pecking, hopping, flying, yes. But snapping at the air with their beaks? Not so much.

So I’m not sure that babies will react to this sign in the same way that adults do. The sign feels self-explanatory to us because we have a lot more experience — including exposure to cultural depictions of birds and bird behavior. In effect, we have been trained to make all sorts of associations that babies don’t yet know about. So babies can learn the sign for “bird,” but they may not reap the same benefits from it’s iconic features.

Maybe this helps explain the results of a recent observational study of preschoolers (non-hearing impaired) learning sign language. The children ranged in age from 2 to 6 years, and they tended to have an easier time learning signs that adults classify as iconic.

But there was also a clear age difference. The youngest children didn’t benefit as much from the iconicity of a sign (Goppelt-Kunkel et al 2023). Perhaps it was because older kids had more background knowledge, allowing them to better perceive the connection between sign and referrent.

Then there’s the question of physical dexterity. Is it physically easier to make the signs of ASL? Easier than it is to form the spoken words of English?

The answer might vary depending on which signs and spoken words we compare. But overall, we have no compelling scientific evidence to prove that signing is any less challenging for babies. The dexterity required to form signs is substantial, so much so that babies don’t typically manage to reproduce signs in their correct form (Bonvillian and Siedlecki 2000).

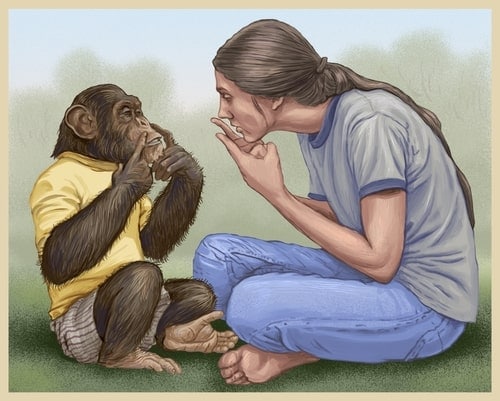

Finally, I wonder if some of people are influenced by the example of ape language studies.

I know I thought of it when I first heard of baby sign language. Admittedly, it was a professional reflex on my part, because of my background in behavioral ecology, primates, and the evolution of intelligence. But I suspect many of my readers have heard about the signing apes.

Years ago, researchers concluded that nonhuman primates lacked the necessary anatomy to mimic human speech. But they wanted to see if apes had the ability to learn language. So they tried teaching them to communicate with hand gestures and visual symbols, and they were successful.

A number of individuals (including the chimpanzees Washoe and Sarah, and the bonobo, Kanzi) have shown they can communicate ideas and answer questions by using non-vocal symbols.

There is a certain parallel with babies. The human infant’s vocal tract is also shaped differently, limiting the range of speech sounds that a baby can make. Yet we know they understand a great deal. So perhaps babies, like nonhuman apes, are anatomically incapable of speech, yet capable of learning symbolic gestures.

It’s an appealing analogy for those of us interested in zoology and human evolution. But with greater scrutiny, it falls apart.

First, the premise about vocal tracts is wrong: You don’t need an adult human’s vocal tract to speak.

For example, research suggests that it would be possible to speak intelligible English (and other languages) with the vocal anatomy of a macaque monkey (Fitch et al 2016). You can listen to a reconstruction here.

So the reason these creatures don’t speak isn’t that their vocal tracts fail them. Instead, it’s likely a failure of the brain: Nonhuman primates lack the precise neural control needed to produce speech (Fitch et al 2016).

By contrast, human babies show a lot of control quite early in life. Between 12 to 20 weeks postpartum, human babies are already capable of matching the vowels they hear adults make (Kuhl and Meltzoff 1996). And by the time canonical babbling emerges, babies have mastered the articulation of many common syllables.

Second, it’s wrong to assume that it’s easy for nonhuman apes (or human babies) to mimic adult human hand gestures. It isn’t!

The human hand is a marvelous, species-specific adaptation. As noted, many linguistic hand gestures require substantial dexterity and control. Such skills aren’t part of a nonhuman ape’s repertoire, so researchers shifted long ago from trying to teach apes symbolic hand gestures. Instead, they focus on systems that use visual symbols on a board.

So if we really wanted to apply an ape language analogy, we’d be teaching our babies to communicate by pointing to pictograms.

But pointing is useful for much more than this. When babies learn to point, they experience a major breakthrough in communication. They can direct our attention to things that capture their interest, and, if we’re responsive, it’s a golden learning opportunity.

When your baby points to a horse, you can immediately provide the label, saying “that’s a horse.” Experiments suggest that babies quickly learn new labels this way.

And that brings us to the really important lesson from research on language acquisition: Children learn language best when we talk with them, one-on-one, and use nonverbal cues — like pantomime and pointing — to get our meaning across.

So whether your baby learns to speak first or sign first, you can give your baby’s language development a boost by enriching your talk with lively, easy-to-parse gestures.

More information about language and learning

To read more about the remarkable importance of gesture for learning, see this evidence-based review. There I talk about the role of gesture not just in learning language, but also in learning mathematics and physics.

And for more about baby signing, be sure to read this article, where I tackle several questionable claims made about baby sign language programs, and share the fascinating research on “transparent” parental communication.

Finally, for other articles about the emergence of language, see these:

- How to support language development in babies

- When do babies speak their first words?

- The effects of television on language skills

- Talking to babies: How face-to-face communication helps infants “tune in”

- The science of gestures

References: Can babies sign before they can speak?

Anderson D and Reilly J. 2002. The MacArthur Communicative Development Inventory: Normative data for American Sign Language. Journal of Deaf Studies and Deaf Education 7: 83–106

Bonvillian JD, Orlansky MD, Novack LL. 1983. Developmental milestones: sign language acquisition and motor development. Child Dev. 54(6):1435-45.

Bonvillian JD and Siedlecki T. 2000. Young children’s acquisition of the formational aspects of American Sign Language. Sign Language Studies 1(1): 45-64.

Fenson L, Dale PS, Reznick JS, Bates E, Thal DJ, Pethick SJ. 1994. Variability in early communicative development. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev. 59(5):1-173.

Fitch WT, de Boer B, Mathur N, and Ghazanfar AA. 2016. Monkey vocal tracts are speech-ready. Sci Adv. 2(12):e1600723.

Folven RJ and Bonvillian JD. 1991. The transition from nonreferential to referential language in children acquiring American Sign Language. Developmental Psychology, 27(5): 806–816.

Emmorey K. 2023. Ten things you should know about sign languages. Curr Dir Psychol Sci. 32(5):387-394.

Goppelt-Kunkel M, Stroh AL, and Hänel-Faulhaber B. 2023. Sign learning of hearing children in inclusive day care centers-does iconicity matter? Front Psychol. 14:1196114.

Hendery R and McConvell P. 2013. Mama and Papa in Australian languages. In Patrick McConvell, Ian Keen and Rachel Hendery (eds.), Change in Kinship Systems. Utah: University of Utah Press. 215–236.

Kuhl PK and and Meltzoff AN. 1996. Infant vocalizations in response to speech: Vocal imitation and developmental chang. J Acoust Soc Am. 100(4 0 1): 2425–2438.

Lillo-Martin D and Henner J. 2021. Acquisition of Sign Languages. Annu Rev Linguist. 7:395-419.

Meier RP. 2016. Sign language acquisition. Oxford Handbooks Online. DOI: 10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199935345.013.19

Schneider RM, Yurovsky D,and Frank MC. 2015. Large-scale investigations of variability in children’s first words. In D.C. Noelle, DC, R. Dale, A. S. Warlaumont, T. Matlock, C. D. Jennigs, and P. P. Maglio (eds): Proceedings of the 37th Annual Conference of the Cognitive Science Society, 2210–2115.

Image of infant boy making hand gesture by Ground Picture / shutterstock

image of baby chomping on bottle by PeopleImages / istock

image of baby sitting on the floor with parents by zamrznutitonovi / istock

Drawing of woman signing with chimpanzee by Anatoly Shapoval / shutterstock

Content last modified and updated 4/2024. Portions of the text derive from earlier versions of this article, written by the same author.