It’s natural for young children to experiment with telling lies. But their readiness to lie depends a lot on the social environment. When adults attempt to control children through threats and punishments, kids are more likely to cover-up their transgressions. By contrast, children are less likely to lie when they believe adults value and celebrate truth-telling.

How powerful are these effects, and what can we do to foster honesty? Here’s a closer look at the research, and some evidence-based insights for motivating kids to tell the truth.

The costs and benefits of truth-telling

We’ve all experienced the impulse: We’ve done something wrong, and we want to hide it. Should we lie about it, or confess?

Victoria Talwar and her colleagues knew that children, like adults, are savvy to the costs and benefits of truth-telling. But what influences them the most? Are kids easily swayed by moral appeals? Promises that their honesty will make us happy? Or are they mostly worried about being punished for their wrongdoing?

The researchers devised a clever experiment to test these ideas, and put more than 370 children (4-8 years old) through their paces. It began with a procedure called the “Temptation Resistance Paradigm,” a standard task that has been used for decades to study lying in children.

The Temptation Resistance Paradigm: A procedure for studying lying in children

A child sits with his or her back to an adult experimenter, and listens to the sound of a toy that the adult is holding. Without turning around to look at the toy, the child has to guess. What is it?

The child plays two rounds of this game, and then the adult explains that she must leave the room for moment. She sets down the next toy on a table behind the child, and reminds the child not to peek while she is away. She explains to the child that they will resume playing the game when she returns.

The woman exits, and, while she’s gone, a hidden camera records the child’s behavior. Then the woman returns and asks the child. “Did you peek?”

How do children respond to the Temptation Resistance task? Typically, most kids can’t resist. They peek. And that was the case in the current experiment: About two-thirds of the children turned around and looked.

But of course that’s only part of the story. The next question is whether or not kids lie about it afterwards. And Talwar’s team wanted to go a step further. They wanted to find out if a child’s tendency to lie depended on the behavior of adults. So the rest of the experiment went this way:

1. The adult returns, and tells the child about the consequences of peeking.

- Half the kids were randomly assigned to hear the woman say, “If you peeked at the toy, you will be in trouble.”

- The other half were assigned to hear a reassuring message. “No matter what happened, I would not be cross at you.”

2. Then — for a subset of children in the experiment — the adult says something more. She makes the case for telling the truth.

- Some kids were randomly assigned to hear the woman appeal to their internal sense of right and wrong. “It is really important to tell the truth because telling the truth is the right thing to do when someone has done something wrong.”

- Other children were assigned to hear an appeal based on external approval. “If you tell the truth, I will be really pleased with you. I will feel happy if you tell the truth.” For kids who’d been previously warned about “trouble,” the appeal came with the additional disclaimer that the woman would “still be cross about peeking.”

- A third set of kids didn’t receive any special appeals to tell the truth. They heard only about the consequences of peeking.

There were 6 groups in all, each representing a different combination of consequences for peeking (“in trouble” and “I wouldn’t be cross”) and appeals for telling the truth.

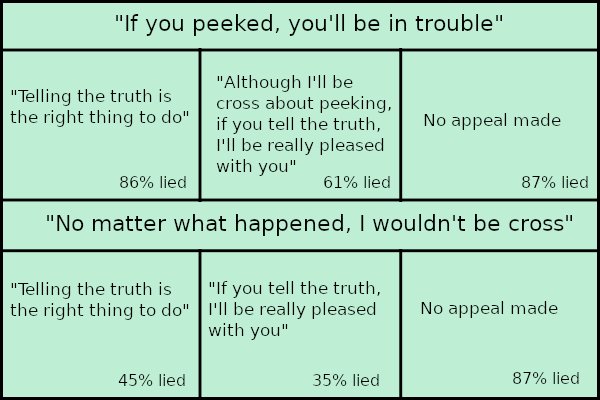

Did it make a difference, what kids heard the woman say? You can see the results for yourself in this graphical summary:

As you may notice, most children – 87% – lied about peeking in the absence of an appeal – internal or external – for telling the truth. It didn’t make any difference if they’d been threatened or not. They lied readily in both cases.

And kids lied at a similar rate – 86% – when they were presented with the internal rationale, but also threatened about the consequences of peeking. Apparently, the appeal to “do the right thing” fell flat when kids believed they would get into trouble for confessing.

By contrast, the external appeal (“I’ll be happy if you tell the truth”) might have been more effective. Among kids who’d been threatened, about 61% who heard the external appeal lied.

But the lowest rates of lying were associated with kids who heard both an appeal to tell the truth and reassurance about the consequences of peeking. Among children who heard both the reassurance and the external appeal, just 35% lied. For kids who’d heard the combination of reassurance and internal appeal, the rate of lying was approximately 45% (Talwar et al 2015).

So talking with kids – providing them with rationales for telling the truth – was helpful. But simply urging them to do the right thing had no discernible effect, not when kids also had reason to believe they would be punished for confessing.

When kids had nothing to fear – or believed that the adult would be pleased to hear the truth – they were less likely to lie.

It’s not terribly surprising, is it? I doubt many adults would confess to a transgression, even a minor one, immediately after being told they would get “in trouble” for it. But of course our willingness to confess depends on more than a single comment from a stranger. We bring lots of prior knowledge and experience to the problem, and for children, it’s much the same.

Some individuals feel relatively secure about making a compromising admission. They anticipate that the consequences will not be severe, that the worst-case scenario is something they can handle. They have faith that they will be treated with understanding and fairness.

Others may perceive higher risks. They reckon that their confession will be received less kindly, or that it will cause damage out of proportion to the offense.

One case in point is the child who finds himself in a highly punitive, authoritarian environment. When every infraction is treated harshly – when authority figures attempt to impose rules that seem arbitrary or unfair – why should he tell the truth?

It’s easy to see how such considerations could bias children in favor of lying. Is there evidence that this happens?

Dishonesty 101: Kids who attend punitive, authoritarian schools are more likely to tell lies

It isn’t easy to test the idea that punitive discipline fosters dishonesty. It would be unethical to randomly assign children to grow up in a harsh, authoritarian setting.

But Victoria Talwar and her colleague, Kang Lee, found a way around this: A natural experiment comparing the responses of 84 young children — 3- and 4-year-olds — attending two, very different schools in West Africa.

All the children lived in the same neighborhood, and tested with similar cognitive scores. But their schools took radically divergent approaches to discipline (Talwar and Lee 2011).

One school was dedicated to authoritarian principles and harsh discipline. Children were routinely slapped, beaten, or pinched for minor infractions, like forgetting a pencil, or getting math problem wrong. Based on the school’s own logs, children witnessed about 40 episodes of corporal punishment each day.

At the other school, there were no observable incidents of physical punishment. Kids who misbehaved were verbally reprimanded, given time outs, or sent to the principal’s office.

Did these experiences affect children’s tendencies to lie? Talwar and Lee administered the “Temptation Resistance” test, but this time they kept things very simple. The adult didn’t issue threats, nor did she make any moral appeals. She simply told the children not to peek, and then, afterwards, asked them if they had done so.

And what happened? The results were consistent with the notion that authoritarianism fosters dishonesty, even in the absence of any explicit talk about “trouble” or punishment: Not only were the children from the punitive, authoritarian school more likely to lie, they were also more competent at lying.

The kids in this experiment were equally likely to sneak a peek regardless of the school they attended. But whereas just 55% of the kids from the non-punitive school lied, a whopping 94% of children from the punitive school lied.

And the kids from the punitive school were far sneakier about it. When asked if they knew the identity of the toy, they seemed to understand the importance of appearing ignorant. Almost 70% said they didn’t know what the toy was, or deliberately made an incorrect guess.

By contrast, only 17% of kids from the non-punitive school responded this savvy way, and their performance was far more typical of children this age. As I explain elsewhere, 3- and 4-year-old liars usually give themselves away in these experiments by blurting out the correct answer.

Does this mean that a harsh, punitive environment trains children to be more devious?

Perhaps not. It’s a single, small study, and the researchers are quick to point out that the results aren’t definitive. For one thing, the children in this study hadn’t been randomly assigned to attend one school or the other. Maybe the kids from the punitive school had something else in common – something that influenced the results.

But we know the people learn through practice, and this applies to lying as with anything else. Moreover, experiments show that young children develop better mind-reading skills when they practice the art of deception.

In one study, many young children spontaneously learned to lie after being asked to play a game that required deception to win. In 10 sessions, they figured out how to deceive, and developed sharper insights into the minds of others (Ding et al 2018).

So we have good reason to think that harsh, punitive, authoritarian discipline creates a context that encourages children to deceive. And the experimental evidence suggests that our moral appeals to tell the truth will have little effect when kids fear punishment.

If we want to discourage lying, we need to make the case that coming clean is worth it. How do we make that case? Research suggests some guidelines.

Tips for encouraging honesty in children

1. Convince your child that you’ll be pleased if he or she tells the truth.

We can do this by making direct appeals. But we can also send the message by showing children we value truth-telling in others.

For example, experiments suggest that children respond to stories about positive role models. They are less likely to lie after hearing about characters who were praised for being honest and admitting to wrongdoing (Lee et al 2014).

Research also indicates that kids pay attention to the feedback that their peers receive for truth-telling. When preschoolers observe that another child’s confession is received with happiness or praise, they are more inclined to disclose their own transgressions (Ma et al 2018; Sai et al 2020).

2. Dispel the notion that bad choices make someone a bad person

Research confirms that children – like adults – will lie and cheat to protect their good reputations (Zhao et al 2017). But some individuals may be motivated by more than the desire to look good. They may believe that wrongdoing is evidence of an innate character flaw — something that can’t be improved or corrected (Dweck 2008). As a result, they may be especially reluctant to admit their transgressions.

So perhaps we can reduce lying in children by teaching them about moral growth. Everybody makes mistakes, and doing something bad doesn’t mean you’re a bad person. The important thing is to make amends and strive to improve. Experiments suggest that adopting an improvement-oriented, “growth” mindset can help kids bounce back from intellectual errors, so it seems plausible that it may help kids cope with moral errors as well.

3. Pay attention to your disciplinary style. When adults engineer environments that are authoritarian and punitive, kids are more likely to develop a habit of lying.

We should understand that harsh, authoritarian control sets the stage for deception. It increases a child’s motivation to lie — to cover-up, rather than confess, a transgression.

More reading about the effects that adults have on children’s honesty

For more information on the impact that adults have on children’s truth-telling behavior, check out these Parenting Science articles:

- “Bad role models: What happens when adults lie to children?

- “Why kids rebel: What kids believe about the legitimacy of authority”

And you can learn more about the fascinating development of lying in my articles:

- “At what age do children begin telling lies?”

- “Compassionate deception: Do children tell lies to be kind?”

In addition, for more information about fostering desirable social skills, see my evidence-based social skills activities, as well as these articles about

Finally, you can learn more about the ways that adult-created environments influence children’s decisions, see my article, “Marshmallow test: Delayed gratification isn’t about willpower.”

References: Punitive environments encourage children to tell lies

Ding XP, Heyman GD, Fu G, Zhu B, Lee K. 2018. Young children discover how to deceive in 10 days: a microgenetic study. Dev Sci. 21(3):e12566

Dewck C. 2008. Can personality be changed? The role of beliefs in personality and change. Current Directions in Psych Science 17(6):391-394.

Lee K, Talwar V, McCarthy A, Ross I, Evans A, Arruda C. 2014. Can classic moral stories promote honesty in children? Psychol Sci. 25(8):1630-6.

Ma F, Heyman GD, Jing C, Fu Y, Compton BJ, Xu F, Lee K. 2018. Promoting honesty in young children through observational learning. J Exp Child Psychol. 167:234-245.

Sai L, Liu X, Li H, Compton BJ, Heyman GD. 2020. Promoting honesty through overheard conversations. Dev Psychol. 56(6):1073-1079.

Talwar V, Arruda C, Yachison S. 2015. The effects of punishment and appeals for honesty on children’s truth-telling behavior. J Exp Child Psychol. 130:209-17.

Talwar V and Lee K. 2011. A Punitive Environment Fosters Children’s Dishonesty: A Natural Experiment. Child Dev. 82, 1751-1758.

Zhao L, Heyman GD, Chen L, and Lee K. 2017. Telling young children they have a reputation for being smart promotes cheating. Developmental Science 23(3) e12585.

image of girl behind fence by istock / Eugene Nekrasov

Green table of experimental outcomes by Parenting Science

content last modified 10/1/2021