If you care about the progress of STEM — science, technology, mathematics, and engineering — you already know the bad news. Around the world, rationality is under attack. Politicians deny the facts. Adults reject the scientific evidence. But the good news is it has never been easier to find excellent books, games, and applications for teaching children about STEM concepts. Here are a few such resources, some of which I’ve mentioned in my articles for Parenting Science. I’ll be adding more in the future.

Full disclosure: I include links to items that can be purchased through Amazon.com. As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases. This means that (at zero cost to you) I will earn a commission if you click through the link and finalize a purchase.

Activities and experiments

Want to conduct a variety of fascinating experiments at home — experiments that illustrate surprising phenomenon, and require only items you already have on hand?

A classic from my own childhood, written and updated by the wonderful Vicki Cobb, is Science Experiments You Can Eat, available from Amazon (commission earned). In addition, check out Crystal Chatterton’s Awesome Science Experiments for Kids: 100+ Fun STEM / STEAM Projects and Why They Work (commission earned). A Chemist by training, Chatterton doesn’t just tell you what to do. She also explains — clearly and very concisely — the “hows and whys” of what you’ll observe. An excellent resource for families with elementary school kids.

For younger children, check out my Parenting Science pages about activities and experiments for preschoolers.

Astronomy and physics

The night sky used be a good recruiting tool for careers in STEM. Nowadays, light pollution makes it difficult for many children to see an awesome, starry sky. But there are excellent resources for budding astronomers and physicists.

The NASA website features many free online games and activities related to outer space exploration and astronomy.

In addition, I recommend the Professor Astro Cat books by physicist Dominic Walliman and illustrator Ben Newman, which can be purchased from Amazon (commissions earned). In Professor Astro Cat’s Frontiers of Space, Walliman provides kids with an overview of space exploration. Professor Astro Cat’s Atomic Adventure teaches kids about physics. There are also volumes about the solar system, rockets, and stargazing. These books are smart, engaging, and humorous. They illustrations are bold and eye-catching, with an early Space Age, retro feel.

Kids will also be inspired by the books of David Aguilar. His Space Encyclopedia: A Tour of Our Solar System and Beyond (National Geographic Kids) is beautifully illustrated with photographs and awesome, naturalistic paintings. Again, the links here will take you to Amazon (commissions earned).

Computer programming

Yes, kids can learn to code — and it can boost their interest in programming and robotics.

For example, in one experimental study, 6-year-old girls were taught how to program a robot with simple commands (forward, backward, right, left, repeat).

After just 20 minutes of play, the kids were interviewed about their attitudes. Compared with girls in a control group, the girls who had just programmed expressed greater enthusiasm for programming, and more confidence in their ability to use robots (Master et al 2017).

But where and how should children begin?

Get a Scratch account — for free!

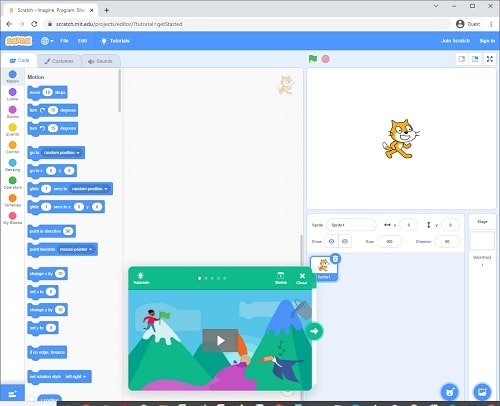

Researchers at MIT have developed an online programming environment for kids. As the folks at MIT note, it’s called “Scratch,” and it’s ” a project of the Scratch Foundation, in collaboration with the Lifelong Kindergarten Group at the MIT Media Lab. It is available for free at https://scratch.mit.edu.”

With Scratch, kids select visual programming elements and learn to combine them into sequences of code. There are other programming platforms for kids, but Scratch has special features that I really like:

- Creativity and versatility rule. Kids can create animations, arcade games, interactive stories, chat programs, random response generators, advanced platform games, calculators, and homework drills.

- Kids join a community. They can post and share their creations with others.

- The community is moderated by people at MIT.

Scratch is aimed at kids ages 8 and up. For younger children — ages 5-7 — MIT researchers have also created Scratch Junior. It avoids text commands in favor of purely visual ones, and, like Scratch, it’s free.

You don’t need any books to using Scratch, but I recommend one — especially if you have no experience with introducing programming to kids. Here are some, with links to Amazon (commissions earned):

DK publishes a number of Scratch workbooks for young children, including DK Workbooks: Coding in Scratch: Games Workbook (commission earned). Motivated children as young as 5 might use these successfully — if they work alongside and adult to help them.

For older kids, How to Code in 10 Easy Lessons: Learn how to design and code your very own computer game (commission earned) is an excellent beginner’s book for anyone who is clueless about programming. It presupposes no prior knowledge or experience, and functions as a kind of general orientation that can be completely quickly. In addition to introducing kids to Scratch, the book also includes some exercises in HTML. The book is recommended for kids age 8 and up. And check out the sequel, How to Code 2.0: Pushing Your Skills Further with Python (commission earned).

Another good starting point for older kids (age 8+) is Jon Woodcock’s excellent Coding Games in Scratch (commission earned). Unlike How to Code in 10 Easy Lessons, this book focuses exclusively on Scratch, and it’s a much longer work. It takes kids, step by step, through the creation of eight games.

For older kids who’ve already learned the basics — or who can catch on quickly — I also like Al Sweigart’s Scratch Programming Playground: Learn to Program by Making Cool Games (commission earned). Sweigart walks the reader, step by step, through the programming of each project, illustrated with screenshots. The culminating project is an advanced platform game. The book does an excellent job of teaching readers how to solve certain types of problems in Scratch (like how to clone objects, or make them split in two, or bounce off walls). It also invites kids to come up with their own modifications. What it doesn’t attempt to do is teach kids the sorts of programming fundamentals you’d find in a secondary school computer science textbook.

If that’s what you’re looking for, you should take a look at Majed Marji’s Learn to Program with Scratch: A Visual Introduction to Programming with Games, Art, Science, and Math. Both books are aimed at kids age 10 and up.

Computer experimentation

Maybe you don’t have a computer for your child to code with. Or maybe you’d like to demystify the parts of a computer by putting one together at home. Or maybe you have an older kid who would like to build a computer-based weather station, security camera, robot, or video game console.

What’s the solution? The Raspberry Pi — a very small, very cheap computer that runs on the Linux operating system, as well as Raspbian (an operating system made expressly for Pi computers).

Created by a charitable organization in the U.K., the Raspberry Pi comes in several models, ranging from the bare-bones Pi Zero, to the more advanced models of Raspberry Pis 3 and 4.

If you’re new to this sort of thing, you can by a Pi starter kit. Kits vary in what they contain. A few years ago, my family had good luck with a Raspberry Pi 3 complete starter kit from Vilros that included the computer, a case, a power supply, 2 heat sinks, and a micro SD card preloaded with the installer software (NOOBS) that helps you set up the operating system of your choice. These days, the latest version is the Raspberry Pi4. So shop around and determine what sort of model and package is most suited to your needs. Whatever you choose, keep in mind that you will also require the usual peripherals — a keyboard, a mouse, a monitor.

Learn more about the Raspberry Pi, and its active community of users, by visiting The Raspberry Pi Foundation’s website.

Evolution and ecology

My own background is in behavioral ecology and evolutionary anthropology, and I’m a lifelong paleontology geek. So I’m biased. But there are objective reasons to think that dinosaurs are an outstanding way for children to learn important concepts in biology. Research suggests that states of curiosity enhance learning (Gruber et al 2014), and few topics can excite a child’s curiosity more than dinosaurs!

In this Parenting Science article, I offer tips for turning your child’s interest in dinosaurs into a passion for science, and I suggest several excellent books for teaching biological concepts, available for purchase from Amazon (commissions earned).

Among these volumes is the storybook, How the Piloses Evolved Skinny Noses (commissions earned), created by researchers and tested on children between the ages of 5 and 8. In experiments, researchers found that simply reading this story aloud to children enhanced their grasp of evolution and natural selection.

Another good book — untested by researchers but beautiful and well-conceived — is Jason Chin’s Island: A Story of the Galápagos (commissions earned). This book presents the development of a volcanic island, showing — in a series of sequential panels — how life first takes hold, and then adapts to changes over time.

To get preschoolers thinking about animal behavior, I like some of the “stage 1” books in the “Let’s-read-and-find-out” series by Harper Collins (commissions earned). How Animal Babies Stay Safe (Let’s-Read-and-Find-Out Science) explores concepts like camouflage and parental care. Big Tracks, Little Tracks: Following Animal Prints (Let’s-Read-and-Find-Out Science, Stage 1) gets kids thinking about the traces that behavior leaves behind, and offers a jumping off point for tracking activities.

For information about tracking, see this article about the cognitive challenges it presents, and these suggested activities for young children.

For older kids ready to learn about the history of life on earth, I recommend Helen Bonner’s highly entertaining When Fish Got Feet, When Bugs Were Big, and When Dinos Dawned: A Cartoon Prehistory of Life on Earth (commissions earned). As the title indicates, it presents information in a comic book format.

Mathematics

As I explain elsewhere, certain types of board games and card games can help young children learn about the number line. In addition, research suggests we can boost early mathematical skills with these preschool number activities. And just a few minutes each day with the right educational app could make a big difference for some children.

For example, in an experimental study of 587 first graders, Talia Berkowitz and her colleagues gave every participating family an iPad, and then assigned some kids to use a free, story-based mathematics app called Bedtime Math. Other children (in a control group) were assigned to use an app that also featured storytelling, but lacked mathematical content.

Over the course of the school year, kids who frequently used the math app with their parents made substantial gains compared with kids in the control group. And the effect most dramatic among children with math-anxious parents (Berkowitz et al 2016). You can get this app for free from the Bedtime Math website.

It shouldn’t really surprise us that well-crafted educational materials can spur achievement, especially if they help parents find ways to explain and teach. Personally, I’m impressed with books by Loreen Leedy, which mostly target children in the early-to-mid primary school grades.

Her book, Measuring Penny (commissions earned) follows a child as she takes a series of measurements of her dog. Leedy explores both standard and nonstandard units of measurement, and inspires readers (grades 2-4) to take up measurement projects of their own. For other excellent Leedy math books, see Mission: Addition, The Great Graph Contest, Subtraction Action, and Missing Math. All are available via the Amazon links provided (commissions earned).

What about older children — kids who’ve learned multiplication, division, fractions, and decimals?

I’ve noticed that many kids get turned off by mathematics because it seems to be about memorizing addition facts, times tables, and simple algorithms. They don’t realize that mathematics can be beautiful, and reveal fascinating patterns. These kids need to be introduced to math as an intellectual subject — not just an occasion for rote memorization. And for this, I recommend two lively, intensely-illustrated books by Johnny Ball, available from Amazon (commissions earned).

In All About Numbers (formerly published under the title, Go Figure!: Big Questions About Numbers), Ball traces the origins of different number systems around the world, and introduces the “magic” numbers (pi, magic squares, the golden ratio, primes, etc) as well as geometry, topology, logic, and chaos theory. Throughout, Ball peppers the text with questions, puzzles, and activities. I believe

In Why Pi? (Big Questions), Ball explores the many applications of mathematics — how humans throughout history have used math to understand the world. Topics include the measure of time, electricity, music, light, navigation, and mapping.

Spatial skills and construction

Speaking of navigation and mapping, there is evidence that young children can learn and use simple maps. Gail Hartman’s As the Crow Flies (commissions earned) helps introduce preschoolers to the concept of mapping by getting them to imagine a bird’s eye view of the ground. For elementary school children, Loreen Leedy’s Mapping Penny’s World (commissions earned) is useful.

For more information about mapping activities, see this Parenting Science article about building spatial skills. There I also discuss the evidence that construction toys can boost spatial skills.

How does it work? Research suggests that playing with blocks helps children learn to model shapes in their minds, so they can anticipate what objects look like from different angles. It also appears that a particular form of play — structured block play — is especially helpful.

If you consider that construction play has other educational benefits, it seems that construction toys — like traditional building blocks, Legos, Mega Blox, and wooden planks — are among the most versatile, enduring, and cost effective toys you can buy.

Can video games boost spatial skills? I think the evidence is pretty persuasive. In experiments, people assigned to play action video games (first person “shooter” games) acquired better mental rotation abilities (Green and Bavelier 2007; Feng et al 2007; Boot et al 2008). To date, at least one study has also found benefits from playing the classic game of Tetris (Terlecki et al 2008).

References: STEM books for kids

Berkowitz T, Schaeffer MW, Maloney EA, Peterson L, Gregor C, Levine SC, Beilock SL. 2015. Math at home adds up to achievement in school. Science 350 (6257): 196-198.

Boot WR, Kramer AF, Simons DJ, Fabiani M, and Gratton G. 2008. The effects of video game playing on attention, memory, and executive control. Acta Psychol (Amst). 129(3):387-98.

Feng J, Spence I, and Pratt J. 2007. Playing an action video game reduces gender differences in spatial cognition. Psychol Sci. 18(10):850-5.

Green CS and Bavelier D. 2007. Action-video-game experience alters the spatial resolution of vision. Psychol Sci. 18(1):88-94.

Gruber MJ, Gelman BD, Ranganath C. 2014. States of curiosity modulate hippocampus-dependent learning via the dopaminergic circuit. Neuron. 84(2):486-96.

Master et al. 2017. Programming experience promotes higher STEM motivation among first-grade girls. J Exp Child Psychol. 160:92-106.

Content of “STEM books for kids” updated 11/10/2023

Image credits for STEM books for kids

image boy boys reading by istock / mangpor_2004

Screenshot of Scratch obtained by Parenting Science under Creative Commons license CC BY-SA 2.0. Scratch image is copyright the Scratch Foundation.